How Manny Medina Created a Billion Dollar Company as a Tech Leader of Color

When we published the first annual People of Color in Tech Report in September 2020, we knew our readers would get a ton of value from hearing the stories of tech leaders straight from the source.

We’re kicking off the People of Color in Tech Conversations series with an inspiring conversation with Manny Medina, CEO of Outreach—a heavyweight player at the top of the sales enablement market and the most popular sales engagement platform on TrustRadius.

In this exclusive interview with TrustRadius CEO Vinay Bhagat, Manny goes in-depth into the experiences that led to him becoming a successful Latino entrepreneur in the United States.

Key Takeaways From This Conversation:

- Tenacity can help POC entrepreneurs with non-traditional backgrounds break into tech.

- Fundraising can be difficult for POC. Maximize opportunities by playing to your strengths.

- Prioritize diversity and intersectionality throughout your career.

Click here to view a transcript of this Conversation.

Why POC Founders like Manny Struggle to Get Funding

Big thanks to Manny for sharing his incredible story and insights for the People of Color in Tech Conversations series.

Manny speaks above about how he dealt with biases against his ethnicity when looking for funding, and research supports his belief that other founders experience the same thing. According to data from Morgan Stanley, there’s a measurable gap in funding for POC founders today. The 2020 People of Color in Tech Report confirms that POC founders are up against an industry where unconscious bias affects everything from recruiting to funding.

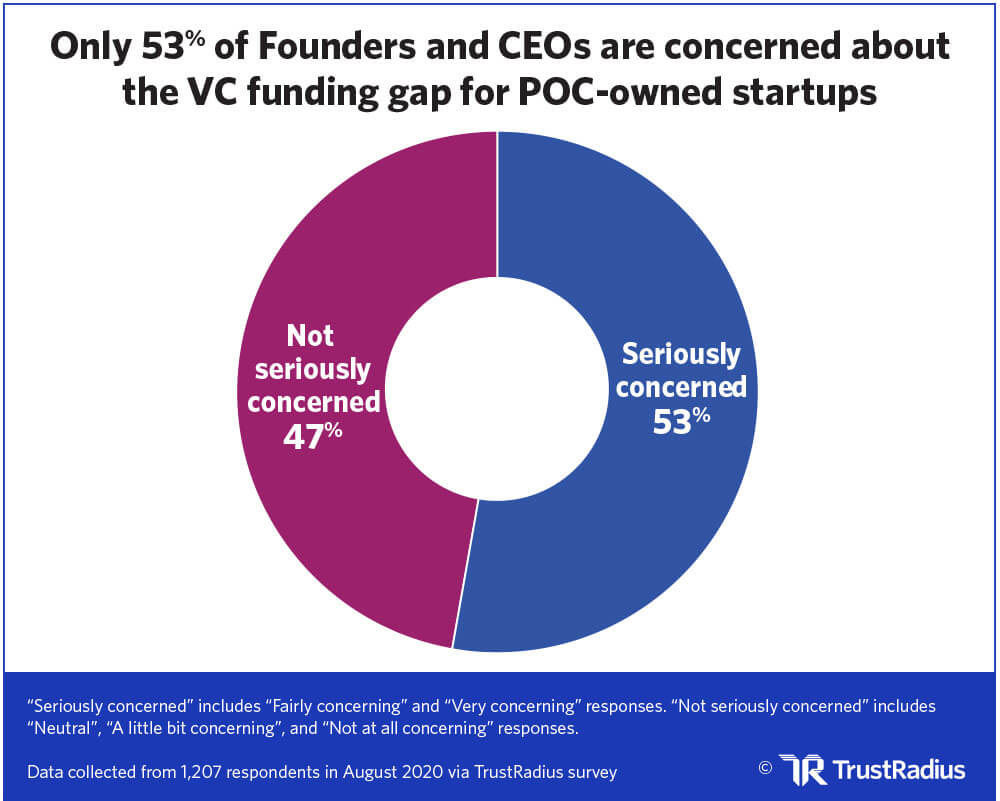

Our recent survey of 1,207 tech professionals found that there is a disconnect between those that are concerned about this issue. 65% of respondents were concerned about the funding gap—but only 53% of founders, CEOs, and those with the capital to fund startups, were seriously concerned.

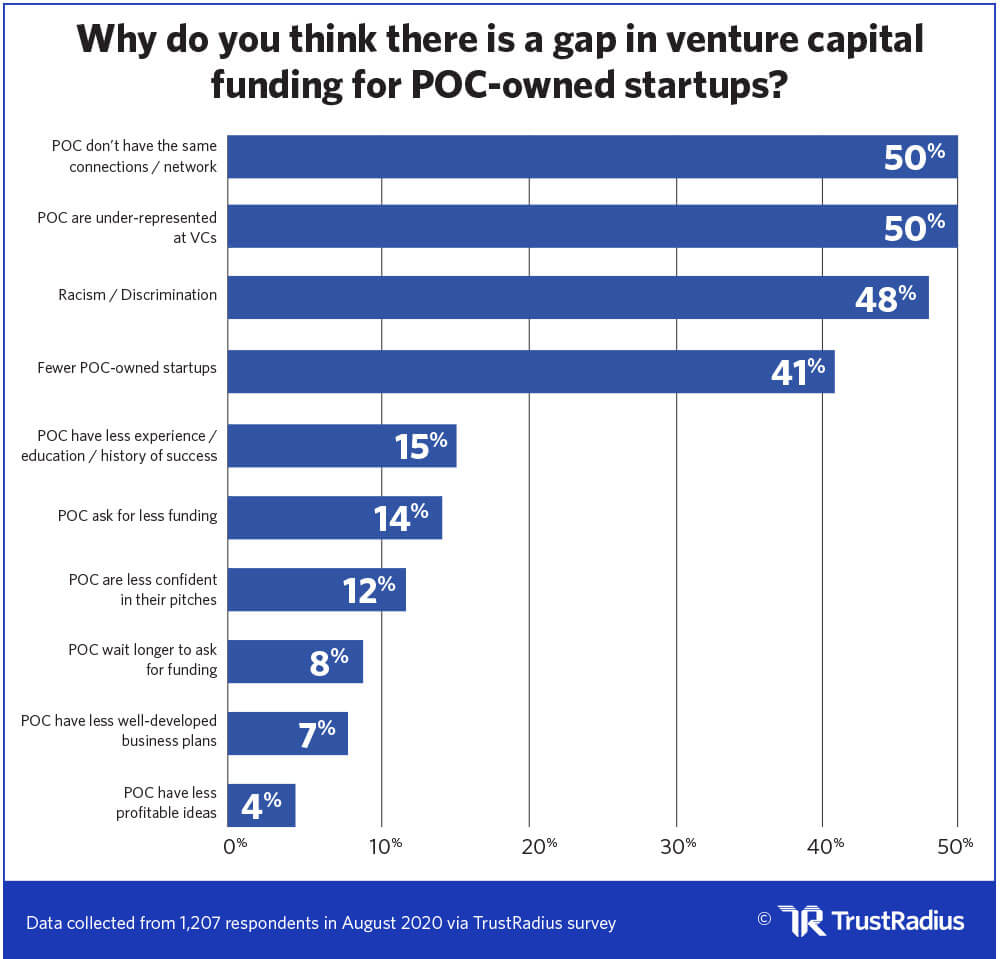

Additionally, we asked respondents across all titles to share why they thought the funding gap exists. The large majority of tech professionals blame this gap on the fact that POC founders don’t have the same networks or opportunities as white founders.

In order to create real change in the tech industry, we have to listen to stories like Manny’s. We have to honor the founders who beat the odds. And we have to raise awareness about the inherent inequality that still exists in tech today.

To learn more about these issues, read the full TrustRadius 2020 People of Color in Tech Report. Then take action and start having conversations with your colleagues, employees, and friends. Together we can make a difference.

Conversation Transcript

Moving to the U.S. and Starting a Tech Career

Vinay: Manny, we really appreciate you taking the time to speak with us today. I know you grew up in Ecuador but talk to us about your story. How did you get into the tech industry?

Manny: I think my story is a little unique in that I didn’t grow up with tech and I didn’t grow up with computers. I grew up sort of lower-middle-class in Ecuador. Middle class in Ecuador is different from, say, middle-class in Argentina. In the middle-class in Argentina you have a little money, you travel on holidays and for festivities with the family. Our middle-class is a little lower than that, in that I was shipped over to family on my summer break.

I didn’t really have any sort of formal or informal exposure to computers until I was in high school. And the school bought a bunch of computers, but they were oversubscribed right away and were mostly used by people who already had computers at home to continue the stuff that they were doing at home and at school. I didn’t have any interest.

I spent my summers growing up in a beach town and then during the school year, I was the classic Ecuadorian kid. I would do my homework and go outside and play soccer until it was time to eat and go to bed. So, that’s my upbringing.

And then during the summers, I would go to this beach town and I would work whatever chores that needed to get done. My stepmom’s family owned shrimp farms so I would help at the shrimp farm in whatever they needed. Sometimes it’s harvest which is at night, sometimes it’s just feeding.

Once I got into college, that’s when computer engineering came up as a major in the university. I did my first two years and then I went into my first year of computer engineering and that blew my mind. Computer engineering or computer science was such an open field for anything. You can invent pretty much anything you want. Any problem that you can articulate, you can write it in code, and that’s just mind-blowing, right? Because there’s no physical limits in my mind as to how you could implement it in code.

So, I started going down the computer science route: one, two, three classes, etc. and then I transferred to the U.S. because my dad came upon a job that was paying in dollars, and he said, “Look, I can pay for your college in dollars. If you wanna go study in the U.S., you could.” So, I transferred.

I went to Stevens where I continued my computer science education, and even though I bought a computer in Ecuador, it wasn’t until I got to Stevens that I got really into computers and into computer science. I realized that I was pretty good at it. I had a faculty for solving problems and I did a few internships here in the U.S. that pointed me in that direction. And I was always in the view that I would get a graduate degree of some sort and then work for a big company and then call it done, right? My parents lived in Ecuador, and I moved to the U.S. I get a bigger, better job, and then my next generation gets a bigger better job, and then at some point two generations out, somebody will be an entrepreneur.

I never thought it will be me being an entrepreneur because my family comes from not only a poor background, but they’re very politically left. Meaning I remember growing up marching for the workers’ cause and the Workers Day celebrations and protesting.

I actually didn’t meet anybody in grad school or in school at all once I came to the U.S. who knew how to burn a tire. Burning a tire is pretty hard to do. And I learned that in college in Ecuador because you’re always protesting either the price of the bus, or the price of the food, or the price of gas, there’s always something to protest about. And you get pretty good at protesting. You know, protesting was kind of like my thing. And I never threw red paint at the U.S. Embassy. You get to do that when you’re in leadership. But I was able to burn a tire, and stop traffic, and make my point heard.

I never thought I was going to be an entrepreneur. It just wasn’t something that crossed my mind.

And as to why I ended up moving to the U.S. and staying in the U.S… I started thinking about, what do you do after you come out of school in Ecuador? As a programmer, your best job, or the best you can hope for, is to maintain software, custom software, or standard software built by one of the big ones. So, you end up maintaining software done by Oracle, SAP, IBM, or Microsoft. You’re a maintenance guy. You go up the ladder of local support or field support and eventually that reports back to the mothership.

So I was faced with this dynamic that I will never be able to write my own code. These will never be my ideas. I will always have to figure out how to fix a problem in the context of somebody else’s idea as opposed to my idea. And it really bothered me that that was the best I could do. Meaning, there was nothing after that, and I have to move somewhere else like Germany or the U.S. to do that. Because of that, I lived in the future. I thought, “I can’t blossom in this particular environment. I have to move to the U.S.”

So I came to the U.S., I finished undergrad, and went to grad school. Then I got my first job programming with a few people that had gone to school with me. My first job was programming, and I was part of a team that was building the billing system for a company called Bell Atlantic. Bell Atlantic eventually became Verizon Communication after the merger with GTE. Bell Atlantic was the largest telecom on the East Coast or was one of the largest in the U.S., period. It was Quest, Bell Atlantic, all the big Bells were represented.

I was working on my code and doing experiments and trying new things. I also realized that I was not the best coder in the team, that there were other people that were much better than me. That’s when it dawned on me that being in raw code was probably not my calling. It was being in technology.

By being able to lead ideas and think of projects, project management, and being the agent of delivery and making it happen, I became more attuned to what I was good at, than actually solving the hardcore code problems that my peers were doing. They were much better at it.

The core difference was the following: My peers would go home and code on their own projects. I would go home and go out, go to the gym, eat out, or do something else, whereas my peers would go home and work on their personal projects. I didn’t have a personal project I was particularly proud of.

That’s when I realized that I wasn’t the best coder in the world, and I went to do something else. You know the rest. I went to grad school and worked at Microsoft, Amazon, that sort of thing.

Facing the Language Barrier

Vinay: So, as a person of color and someone of Ecuadorian descent, you’ve talked about English not being your native language. As you left grad school and worked at some really eminent companies like Amazon, did you face any barriers as a non-native English speaker?

Manny: The barriers are not there in the physical sense. You can’t point to any one thing that happened to me that made it harder. There’s not like a seminal moment. But there’s always this subtext. Now they’re called microaggressions, but back then they didn’t have a name.

When people knew where I was from, that A) I had an accent and B) that I was Latin American, they wouldn’t believe that I was in computer science. That’s not something that you do, right? I’m supposed to be in some kind of manual labor. So, there was this dissonance that I immediately brought into a conversation.

They would immediately speak to me a little slower. The tone would be a little bit more condescending. Their expectations immediately lowered because I was not like everybody else.

That even carried forward to VCs when I was fundraising. I used to get a lot of “No”s at the very beginning. And I know it’s normal to get a lot of “No”s, but a lot of times it was kind of disrespectful.

People would come to several meetings and be clearly interested in our progress and market size, but they just didn’t see me as a CEO. You know what I mean? There’s something wrong with this picture, and they thought it was me, Manny.

Nobody would come out and say it, of course. Nobody would, right? But it just felt weird how people would be interested in what we were working on but the momentum wasn’t there after seeing who I was.

Vinay: What were some of the subtle cues that made you reach the conclusion that they were hung up on you as a CEO because of your background?

Manny: It’s usually after you set up a meeting to go through your pitch. There is a lot of back and forth via email, sending your deck and your talking points. Then they will ask for a meeting. But when I walk into the meeting, people look at me and deflate. With “Manny Medina”, I guess it’s not obvious that it’s Latino, but the moment I show up it’s obvious that I’m a Latino male, right? From then, the meeting takes a different turn.

You can argue that this happens to other people, too. I’ll get evaluations, the same deal, but it will get strung out and people won’t get back to me. I know that this is pretty common with entrepreneurs, but I don’t think my experience is particular just to me. I see other entrepreneurs get the same treatment.

The hardest part was when I was fresh in the U.S. People would talk to me a little bit differently, a little bit more condescendingly. Especially when I would apply for a job, you can hear the pitch and the actual volume of their voice go up. Sometimes I would ask them to repeat themselves and not because they weren’t loud enough, but because there’s probably a word there that I missed or was pronounced too quickly, etc.

And I don’t do it as much as I used to, but as a foreigner, I’m translating on the fly. So, whatever is coming out of your mouth, I’m translating to Spanish, processing, translating it back to English and getting back to you. So, yes, I do need one more cycle than normal people do, than the English speaker would, because I have to translate. Because of that people would just think I’m slow, you know, or just dumb. But instead of speaking a little slower they would speak louder, which was a funny thing.

So, sometimes I would think, “I am a foreigner, I’m not deaf.” You know what I mean? I just didn’t understand what you said. By saying it louder, it’s not gonna make it any better. So, I had to deal with a lot of that. That causes self-doubt. As it is, I’m new to the country, I’m new to entrepreneurship, I’m new to a lot of things. I don’t have the normal background.

And I don’t have the stories. If you’re an entrepreneur, you can read stories of people like you and be inspired by that person and connect with that person on a very fundamental level.

I didn’t have stories to go by. When I was growing up, with entrepreneurship, there was no other Latino immigrant who was making it big. No one that I can go to and say, “I’m going to be like X.”

So, it was hard, because you have to associate with other people, right? I associated with immigrants from Europe, for instance, who had a different kind of hard time. But I had a hard time, too, right? So you have to make your own stories.

Using His Strengths to Raise Funding

Manny: In my case, I had to play to my strengths. So I realized what I may not be the best in. When I walk into a VC room, and they’re all sitting at the big table and looking at me, that’s not gonna be the moment I shine. Especially when I’m not so sure of myself. The moment I shine is when I’m one on one. So, I decided to stop VC funding for a period, like a year, and all I did was raise angel funds.

Because on one on one, you will get to know me, you’ll get to know my story, you will get to know the market, you will get to know the team. I will convince you to write me a check. It would be a small check, you know, $20,000 or $30,000 or $50,000. But I can do this all day. I can do two or three of these a month. And like that, I raised $400,000 with angel investment.

But what happens when you raise from angels is that all these angels are now monetarily invested in you on a very personal level because they believe in you. Now they’re making the interest of VCs and that’s a different kind of rubric, right?

You create a different kind of respect with somebody like Sarah Banks, or Ellen Levy, or Andy from Thrive Capital. Go make that intro, because that intro is worth a lot. And when they make a statement that they invested, all of a sudden you go from here to here. So, I used that as a way to get around the problem.

I convinced people to believe in me, believe in the team, believe in the idea. And then that got me the credibility that I needed. Because just looking at me, I didn’t inspire that kind of credibility. So I had to go a different route.

Vinay: Now, obviously, you’ve achieved tremendous momentum. Did you face similar issues of either self-doubt or doubt from those second-round investors even though you had these metrics and the story behind you?

Manny: I think it less now because we have a team and the story is more credible, and we have momentum. I also think that there’s a real sort of social awareness in the last year and a half. From the Me Too Movement and Black Lives Matter, too. So, social awareness is becoming a thing.

I also created my own sort of my own self-protection. So, I don’t market when I go raise. I don’t go and talk to 100 to get five turn sheets because you’re gonna take one. I try to be as close as I can to people who understand the story, who could write checks and future rounds. At all times I maintain a group of five to 10 investors, it could be VCs, or it could be public funds, to whom I’m telling the story. So when I do the round, I don’t call everybody. I just call the five people and say, “I’m doing a round, is anybody interested?”

The story and the momentum has superseded the person. So I don’t have to worry about that anymore.

Series A and B, you don’t know anybody. So, you’re building that momentum, and series A, B, and C, it gets a little better because A and B are talking about you. D gets a little bit better and so on and so forth. By the time I got to series E, we closed a month ago. It was sort of like a fait accompli.

I’ve been talking to Sands Capital for a year. They’ve been giving me feedback on pitch, on product, my approach and fundraising, etc, So it was a quick sit down and being, like, “How can we be helpful in this pandemic?” A small check was a way to be helpful, and that was done. So, that’s how I did it. I don’t know how other people do it but that’s been my approach.

Leading From Experience

Vinay: How are you taking the insights and the lessons that you’ve learned as an immigrant, as a non-native English speaker, as an entrepreneur, and running your own company differently? What are some of the things that you’re doing to make your workplace more accepting and more inviting to other people?

Manny: So, first of all, I make that a priority. Making the workplace more inclusive, ensuring that the pipeline has all sorts, independent of color, race, provenance or sexual orientation, etc., and that everybody’s role is represented. Then I work with my team to ensure that all biases of all sorts, subtle biases or implicit biases, are removed.

For instance, one of the things we do for immigrants is that we don’t ask about your immigrant status during the interview. We interview like anybody else. Once we decide we’re going to hire you, then we figure out the mechanism by which we bring you to the company.

And once you’re here, then there’s a point around educating everybody else about it. We had a person that just joined the team and we ran a couple of trainings around trans awareness. We’re at 600 employees and some people are non-gender conforming, so we have to be able to include them, too.

I hear a lot of people not using they/them and saying it’s hard because it’s not conforming to grammar, etc. So accept both sides. Meet people where they are, even if it’s hard for you. We did a little bit of training where we gave some examples of how to use it. How do you make it easy to colloquially bring it in? And how do you correct somebody who is calling you by the wrong pronoun? How do you approach a conversation with a trans person and you want to hear more, you want to know more?

Now we’re doing the same thing on the heels of all this racial unrest. We are putting more attention now to how we do the same thing for people of all colors, Latinx and Blacks. And make sure that we are removing whatever biases we have there.

Discrimination comes in so many forms. And it’s so insidious that you have to work to the point of using the right words, calling it what it is, and defaulting at all times to power and policy as opposed to person.

Your goal too should be like, what in the framework is making this person act the way they do, and bring that level of understanding before you say, this person is doing it because X, Y or Z. And it’s funny. That is a fundamental attribution error that we’re going to have to correct and we’re going to have to correct it as a team. So, how am I different by doing that? You know what I mean?

I don’t want anybody to go through what I went through. I don’t want anybody to be less because of how they speak or where they’re from. And that is a personal motive of mine. That will never happen in Outreach under my watch. You put it out there and you chase it until you get it done.

Making Diversity a Priority

Vinay: A lot of companies struggle with creating a diverse recruiting pipeline. Even if you remove unconscious bias from your recruiting process, just attracting diverse candidates can be challenging. How are you going about that?

Manny: So, we do it a couple of ways. First of all, we set a particular goal. So, for the last year and a half to two years, we have had an implicit goal. It’s been explicit in some teams but not at the company level. It’s been explicit to me.

So, I set it by example, telling the company to go through this. I set the example by saying, “We’re going to move the company to a 50/50 split of women, 50/50 gender split.” Now, this is a little outdated now because we also should have a non-gender split. A non-gender, nominative split. But for now, let’s go men/women, which is easy to measure. I put it out there and I said, “Look, I’m committed to getting the company to 50/50, who else is with me?” And then a few teams stood up, and they came with me.

Now on our team, I have five direct reports out of which four are women. And then that cascades down. Because those women in power bring other women in power. And now we have a lot of teams being either 60/40 or 50/50. As a company, we’re 60/40 and we’re still working on it. We set that goal, and then we hit the goal.

It’s not just about the pipeline. It’s the pipeline, and then the interview process, to make sure that people are not dissuading them from joining. And then after they join, it’s about making sure that they’re being successful, making sure that we track them to get equal opportunity.

We do twice a year salary reviews to make sure that everybody is fairly compensated. So, you have to set up all the systems to make sure that there is not only the pipeline, but as people are getting through it they are being successful.

Now the next turn on the crank is going to be doing the same thing for people of color, of different colors. So we just started talking to Historically Black Colleges and Universities. To start creating a pipeline there, we’re getting help from the AI Academy, we’re getting help from Black Girls Who Code.

We’re just trying to start creating the funnel, but the first instantiation of this is gonna be make sure that our interview process is rid of biases, make sure that our onboarding process is rid of biases, make sure that when they join, we can talk openly about these things and they have a forum and they have a community and they have license and they have agency to thrive in. So, you do both, right? You fix the pipeline, but you have to fix what happens when they’re here and how they thrive. Otherwise, you’re just gonna be churning.

That’s how I think about the problem. This is not a one year journey, it’s a multi-year journey. And the sooner you start, the better off you’re going to be.

I’m not like Amazon. But if Amazon went and said, “let’s make diversity and inclusion a core value” with 110,000 people, it’s just not gonna work without it. You know what I mean?

You do it at the very beginning before the cement sets. And then you sort of rinse and repeat a little bit to make sure that you live it. And you live it by announcing it, by talking about it, by delivering against it, by measuring it, by making it a thing, by celebrating it, and then you live the next thing. So, it’s not scientific, but it is what it is.